The AI Assembly Line

How Ender Migrated a Large React Codebase

1. The Shift

Software used to be about writing code by hand. High-level languages moved the hard part from registers into compilers and runtimes. AI is now moving the hard part from manual implementation into orchestration and control.

The interesting work is no longer “type every line correctly.” It is “specify the behavior, design the system that changes it safely, and control a set of non-human executors that do most of the typing.”

2. Why the Old Model Breaks

The classic model is one engineer, one ticket, end-to-end.

They interpret the spec, write the code, discover edge cases, fix regressions, and push to production. That model assumes the primary constraint is human speed.

Once you add AI agents, the constraint moves. The slow and dangerous parts become how:

clearly you specify the work

well you keep the system aligned with the architecture and domain rules

quickly you detect confident, wrong answers

Agents are fast and literal. They can implement complex patterns quickly. They also lose context, ignore unwritten constraints, and happily ship code that passes local tests while violating system-level expectations.

Treating them like junior engineers fails. They are not junior humans. They are high-speed pattern engines that need strong structure and good guardrails.

The AI Assembly Line is a model that treats this honestly.

3. The AI Assembly Line

Think of development as a pipeline instead of a solo craft.

Work enters as a business need. It leaves as a tested change in production. In between, it passes through a small number of specialized roles:

Technical Product Manager (TPM)

AI Engineer

Resolution Engineer

Each role adds context, reduces ambiguity, and catches specific failure modes. The point is to build a controlled factory for change utilizing AI.

Principles to Follow

Each stage should enrich information, not just pass it along. A requirement becomes a structured spec, which becomes machine-ready work units, which become code and tests.

Feedback should flow upstream. Every failure or surprise at the Resolution stage should change how the TPM structures future work and how the AI Engineer runs the pipeline.

Quality should be checked at multiple layers. Requirements quality, architecture fit, implementation details, and real behavior all need explicit attention.

The pipeline itself is a product. You design it, measure it, refactor it, and version it.

4. Technical Product Manager: Context as a First-class Artifact

In this model, TPMs are context engineers.

A PM or stakeholder asks for “feature X.” A TPM doesn’t write “Implement feature X” and call it done. They dig into why it matters, what constraints the system already has, and which existing patterns must be preserved.

They work with architects to capture boundaries and invariants. They identify safe-to-reuse system patterns. They then break the work into units that an agent can handle: each unit has local context, clear inputs and outputs, examples, and links to relevant code.

A good test is simple. If an agent only saw the artifacts produced by the TPM, could it do the right thing most of the time without guessing? If not, the spec is not ready.

The TPM shifts complexity upfront, where it is cheaper and less dangerous.

5. AI Engineer: Operating the Swarm

AI Engineers treat agents as a fleet.

They assume the agents know a huge amount of generic code patterns, forget anything that is not in their context window, and have no intuition about the specific codebase unless you inject it.

Their job is to turn patterns and constraints into concrete workflows. They encode migration recipes, standard patterns, and architecture rules into prompts, tools, and automation. They decide how to batch files, how to structure inputs, and when to stop and inspect.

They watch the system. Where do agents loop? Where do they generate code that compiles but violates conventions? Where do they repeatedly fail on the same type of change?

Interventions are small but precise. Break a large task into smaller units. Add more examples. Tighten or relax constraints. Add extra checks that use compilers, linters, or tests as sensors.

The core skill is control, not creativity. Observe, detect drift, correct the process.

6. Resolution Engineer: Finishing Where It Matters

Resolution Engineers work at the tail of the pipeline.

They receive partially correct code, structured specs, and clear intent. Their job is to finish the hard parts that agents are not reliable at.

This includes subtle type issues, deeply domain-specific behavior, complex error handling, and performance-sensitive paths. It also includes semantic test changes that should affect behavior.

They examine what the agent did correctly and keep it. They fix what is wrong or missing. They align the result with local conventions and performance expectations.

They also feed information back into the system. If they see the same pattern of failure repeatedly, they turn it into guidance for TPMs and AI Engineers. Over time, the pipeline fails in fewer places.

This role owns the last 10-20% where quality is won or lost.

7. How the Pieces Fit Together

A TPM shapes the work. They define the behavior change, capture constraints, and break the task into units that are small enough for an agent but rich enough to avoid guessing.

An AI Engineer runs implementation. They feed those units into agents, watch the results, and adjust the process to keep the system aligned. Compilers, type systems, and tests act as guardrails and sensors.

A Resolution Engineer completes and hardens the work. They fix what automation could not, adjust tests to match intended behavior, and ensure the system still behaves correctly end-to-end.

All three feed back into the pipeline design. Specs get better. Workflows become more robust. The amount of manual cleanup shrinks.

Each iteration improves both the codebase and the factory that operates on it.

8. Example: Migrating a Large React Codebase

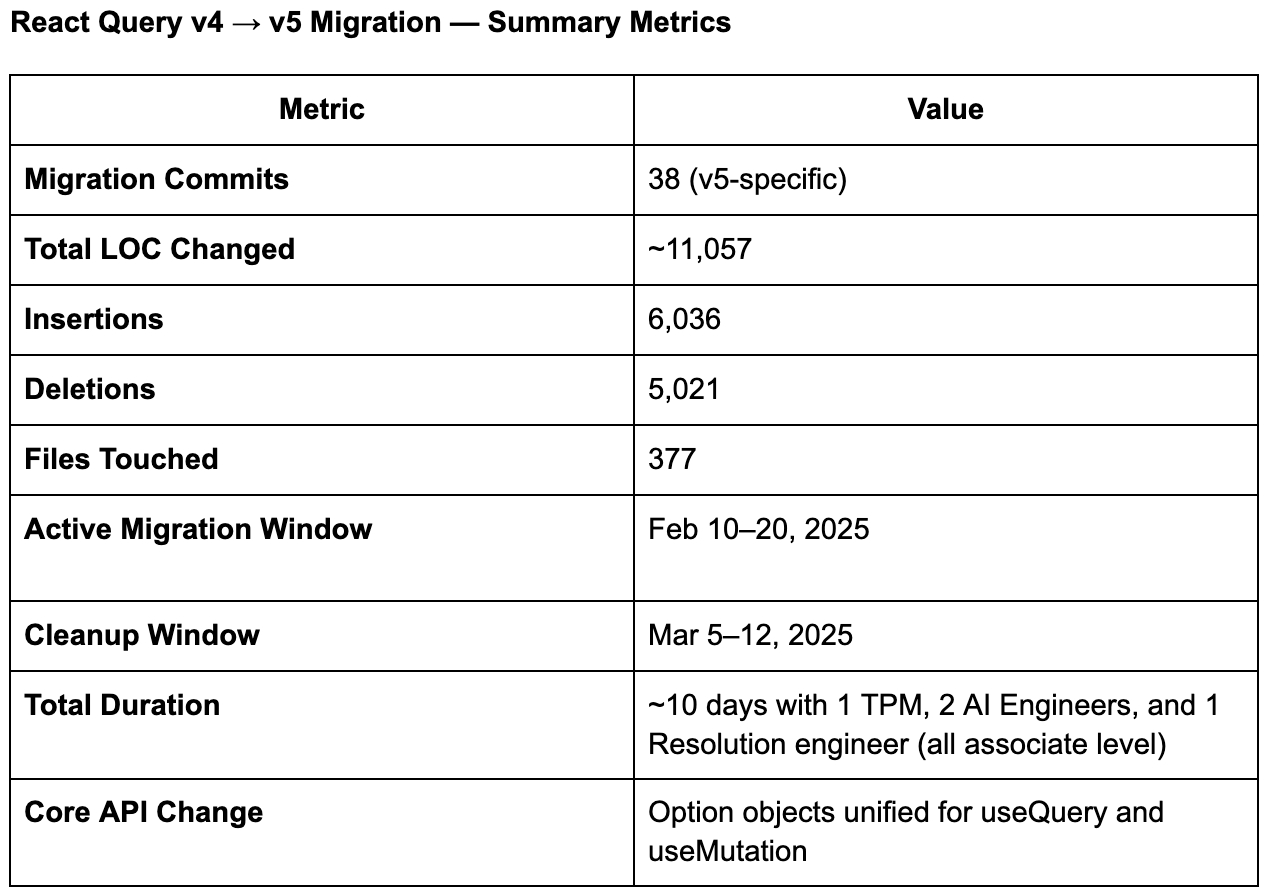

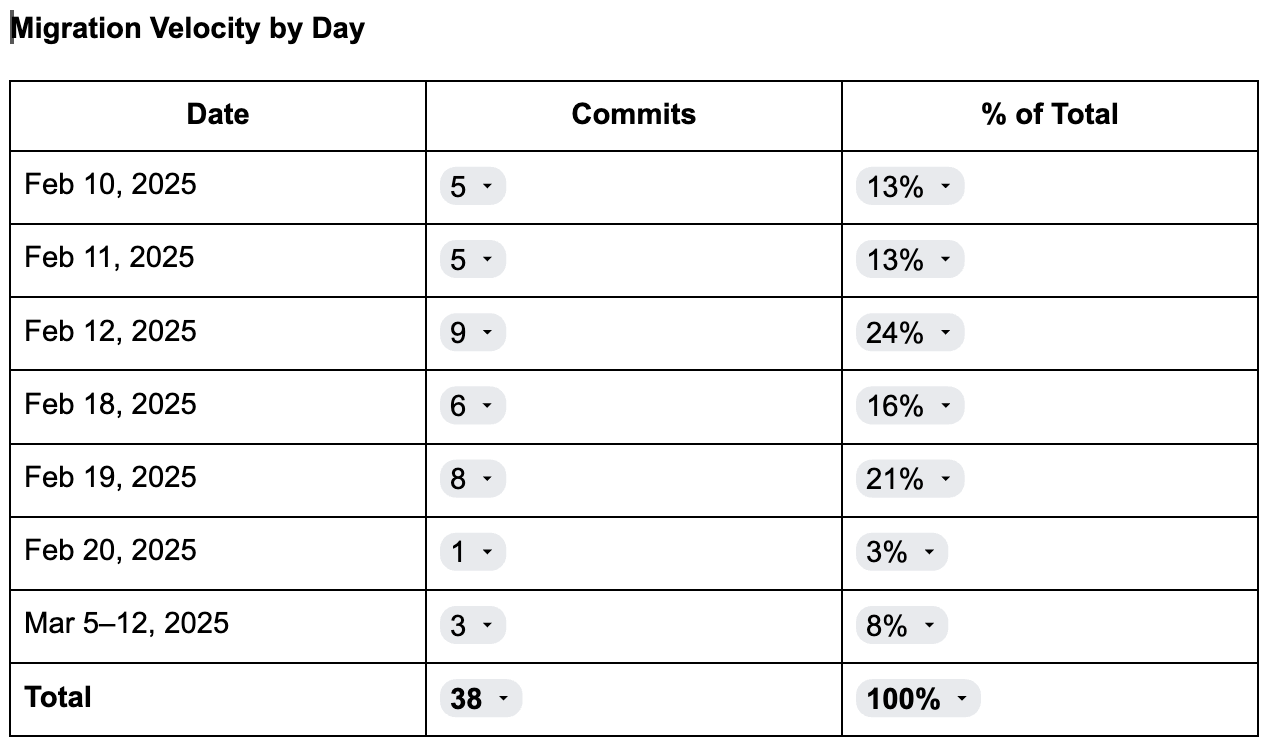

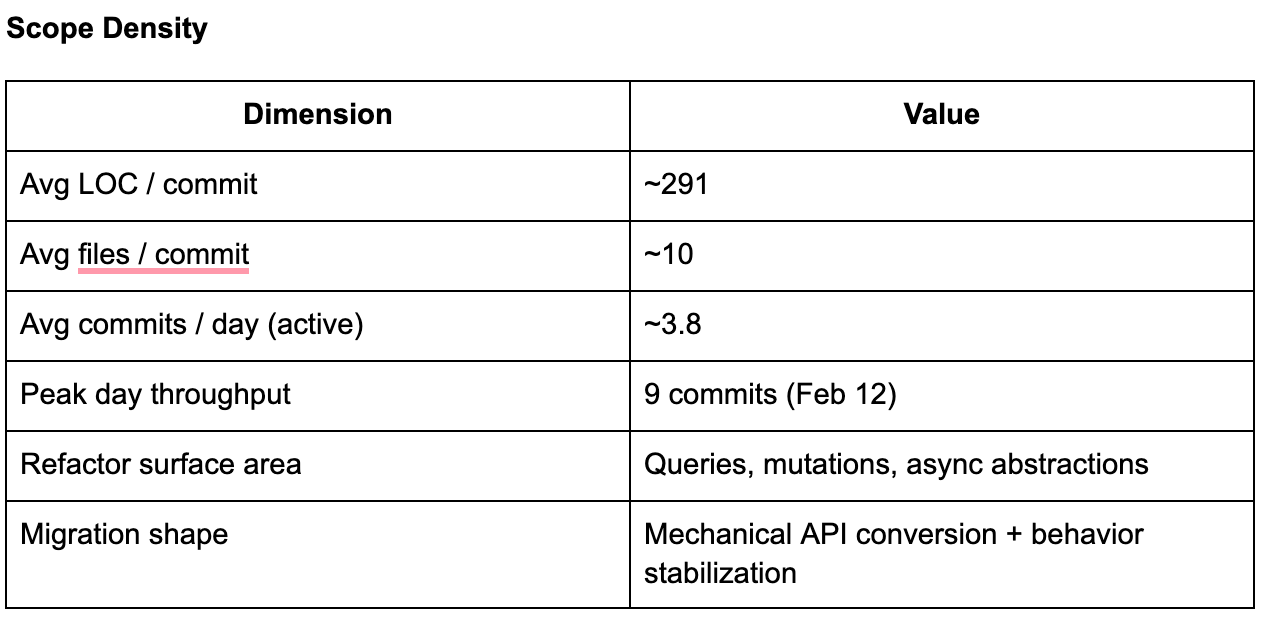

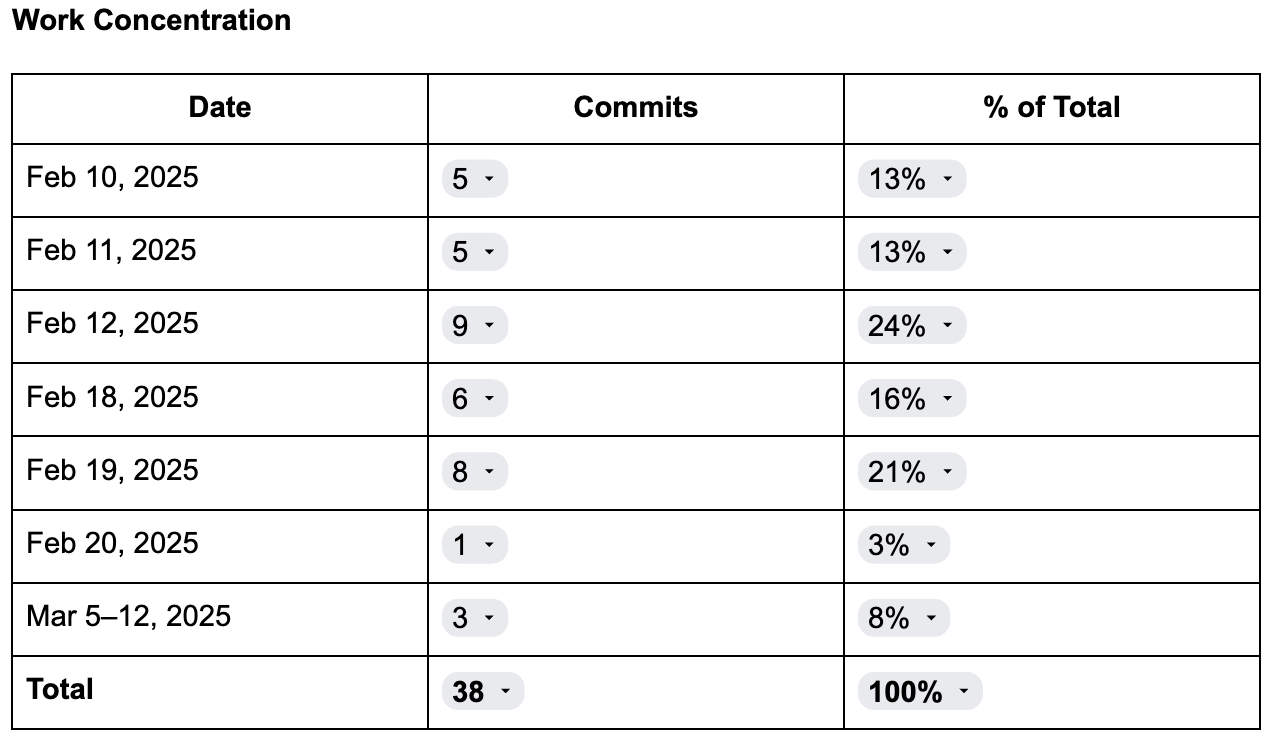

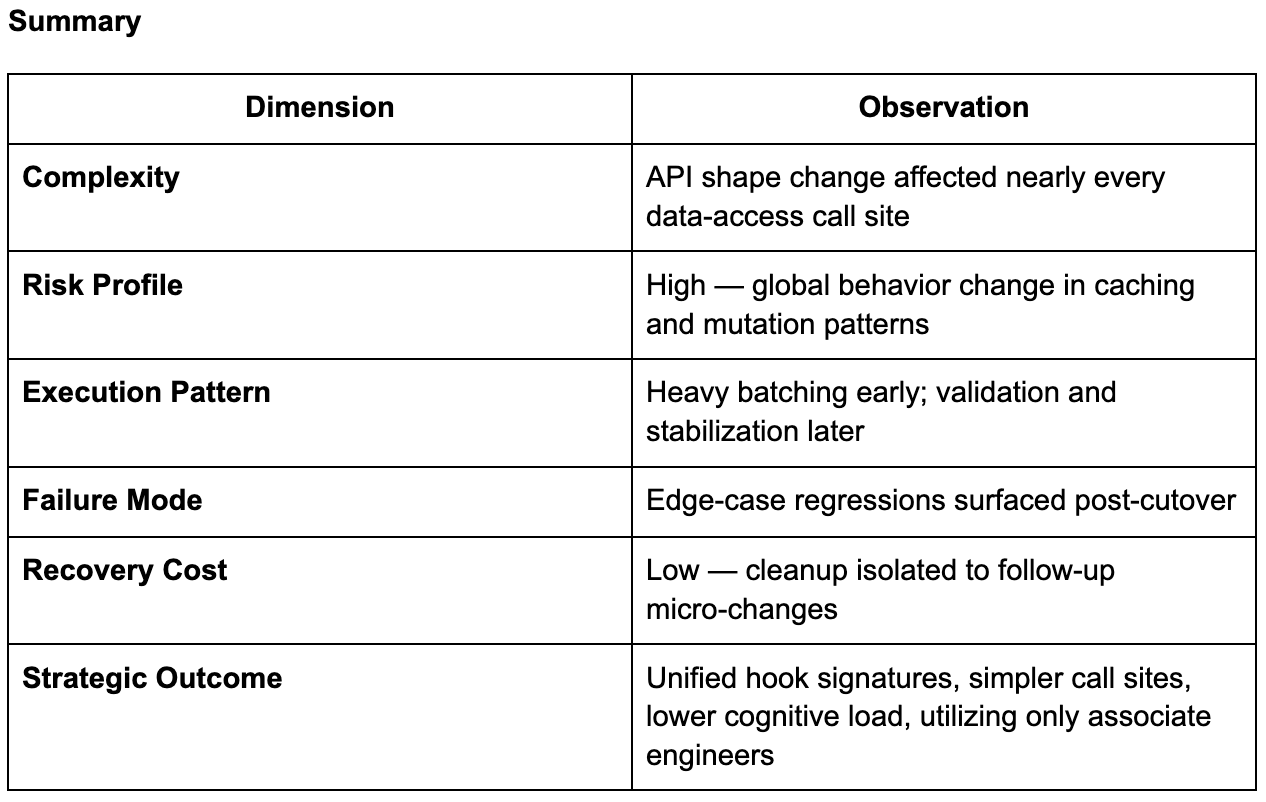

We recently upgraded our large React codebase from React Query v4 to v5.

Handing this to a few engineers and hoping they survive the TypeScript errors is one option. The Assembly Line is what we opted for.

First, the TPM sets the goal: complete the migration with type safety preserved and minimal ad hoc debugging. They upgrade the dependency and config to the new version, run a full TypeScript build, and capture all errors.

They then use AI to cluster errors into patterns. Some are simple signature changes, others are option shape changes, others are behavior changes. For each pattern, they write a short migration recipe that explains what changed, how to fix it, and shows one or two correct v5 examples. They associate each pattern with the list of affected files.

The result is not one giant task. It is a set of structured work units: pattern plus file list plus recipe.

Next, the AI Engineer encodes these patterns into agent workflows. Each workflow takes a pattern, the relevant files, the TypeScript errors, and the examples. They generate tasks like “apply pattern A to these 40 files” with all the necessary context attached.

Developers run agents against these tasks. The agents apply the transformations and use TypeScript errors as guidance and validation. The AI Engineer watches where they fail repeatedly and updates the patterns, prompts, or batching strategy.

Finally, the Resolution Engineer reviews the pull requests. They fix the remaining type issues, subtle behavior changes, and tests that need semantic updates. When they see new sub patterns emerge, they send them back as new or refined recipes. The Resolution Engineer also picks up the PR when the AI Engineer can’t get the agents to reliably fix the issue.

The end result; a task that would have taken weeks took ten days.

9. Making it Real in an Organization

To actually run this model, you need to be deliberate about scope, infrastructure, and structure.

Start with pattern-heavy, high surface area work where the cost of manual effort is large, and the shape of the change is clear. Migrations, refactors, and repeated feature changes are ideal. Do not start with ambiguous new product exploration.

You need infrastructure that can carry rich context. Tickets that can store structured specs, error clusters, and links to patterns. A knowledge base for recipes and examples. A way to manage prompts and workflows. Monitoring that shows where the pipeline failed, not only whether a job ran.

You also need to align people around the pipeline. TPMs must be technical enough to shape work for agents. AI Engineers must sit close to tooling and infra. Resolution Engineers must be treated as high leverage, not as the cleanup crew you bolt on at the end.

Cadence matters. Daily conversations focus on unblocking and acute failures. Weekly conversations focus on process gaps and broken assumptions. Monthly conversations look at throughput, defect rates, and time to change.

If you ignore these layers, the system degrades.

10. Business Impact and the Future of Programming

The AI Assembly Line changes the economics of software.

Development velocity increases because agents handle bulk implementation while humans focus on design and the complex parts. Quality improves because responsibilities are clear and there are multiple chances to catch errors. Senior engineers spend more time encoding patterns and resolving complexity, and less time editing.

Every project trains the factory. The cost of the next similar project goes down. The risk also goes down because the system has seen this class of change before.

Programming stays technical but shifts in focus. Less manual translation of ideas into syntax. More precise specification, orchestration of automated workers, and high-level debugging of systems and processes.

The question is not whether AI will write more of the code. That is already happening. The question is whether you treat that reality as random noise around individual engineers, or build systems and processes to control it.

The teams that build the factory will set the tempo.